How the Fed’s 2% inflation target has become a joke

What justifies a Fed rate cut? Hint: Not the numbers

How the Fed’s 2% inflation target has become a joke

What justifies a Fed rate cut?

Hint: Not the numbers

In making policy the Fed always has to manage risks. Risks are everywhere. The Fed has a dual mandate. We know it has to balance its objective for 2% inflation against maximum employment growth. But how exactly does that translate into policy risk? What does the Fed prioritize to make decisions– and when?

The unemployment rate is up by six-tenths of a percentage point from its cycle low but still at a relatively moderate level, a level that is roughly consistent with what economists think is full employment. The unemployment rate had spent some time at levels that were so low we hadn't seen levels that low for 50 years - hadn't seen levels lower for over 60 years! But that doesn't mean that those kinds of unemployment levels are sustainable.

As the Fed meets, the focus is on the federal funds rate and the Fed has clearly led us - through public statements - to the conclusion that it will be cutting interest rates at this meeting at long last. There has been a certain fiction promoted that the Fed is deciding between 25 basis points and 50 basis points but in truth the economy is doing quite well and there is no imperative for the Federal Reserve to cut interest rates to help the economy at all and certainly not by 50bp. Job growth is slower than it was but it's still plenty fast enough to absorb new entrants into the labor market. The inflation rate has come down but for 40-plus months it's been above the Fed's target of 2%. At some point the Fed needs to reach its target and has to stop promising us that it will get there someday. The vague promise of ‘someday’ begins to look like a big assurance that doesn't have any meat on its bones the longer we go without achieving a 2%, the less it seems that the Fed cares.

As far as I can see, this notion that the Fed could cut rates by 50 or 25 basis points is simply a ‘cover story’ so that the Fed can cut rates by 25 basis points and not look like it has done something outrageous in the heat of a presidential battle that is so hotly contested. The Fed will be able to say ‘well’ we could have cut 50, but we didn't, we instead chose the moderate course.’

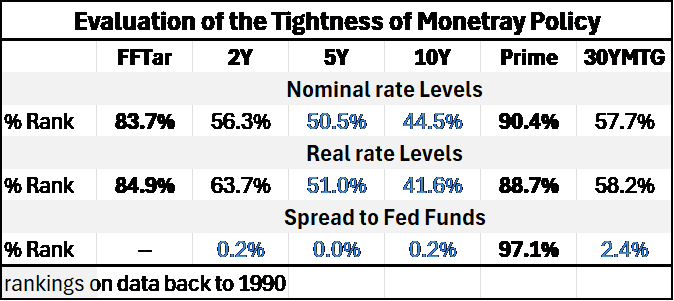

The table (below) helps to flesh out some of the relevant issues by making the point that interest rates in fact are not as high and not as restrictive, not as troublesome, as many people are pretending that they are. In that table there are three different lines of data: one for the nominal rate levels, one for real rate levels, and the other for the spread of market interest rates over the federal funds rate. The table offers not the actual values of the spreads but the ranking of the statistics in the table providing the ranking of the data as they exist in their most recent incarnation in August 2024 over a period back to 1990.

And it’s not the level of interest rates!

The table shows that the federal funds target rate, for example, is at its 83.7 percentile. The target in real terms - the real fed funds rate - is at its 84.9 percentile. The nominal fed funds rate and the real fed funds rate have been higher than their current levels only about 15% of the time. That, in the minds of some people, burnishes the case for the Fed funds rate being too high and the need for the Fed to cut interest rates. Or on second thought does it does it really?

Nominal rate rankings

As we move beyond the entry for fed funds, we see that the ranking for the two year note for nominal rate levels is at it's 56th percentile, for the five year note, it's at its 50th percentile, on the 10 year it's at its 44th percentile, below the 50 percentile mark that marks the median for the period. The prime rate is high at its 90.4 percentile and the 30-year mortgage rate is at its 57.7, percentile above its median, but not especially high

Real rate rankings

Moving on to look at rankings for the real rate levels, the two year is at its 63rd percentile, the five-year Treasury is at its 51st percentile, the 10-year is at its 41st percentile, below its median. Once again the prime is high, at its 88th percentile. The 30-year mortgage rate is at its 58th percentile, above its median, but not tremendously high.

Spreads over Fed funds

The next line gives the spreads to the federal funds rate and here we see the real story which is that the two year note has a spread above the Fed funds rate that is higher 99.8% of the time, the spread of the five-year has never been higher since 1990, the 10 year spread has been higher again 99.8% of the time the prime rate once again still is about as high as it's ever been higher only 3% of the time or so while mortgage rates are also tightly spread to the funds rate and have been higher about 97.6% of the time. Securities yields are spread BELOW the Fed fund rate not above it and that mitigates the impact of the high Fed funds rate on markets and on the economy!

The story, in case you're having to figure it out, is that while the federal funds rate is high in nominal and real terms, market rates are still largely inverted and their spread relative to fed funds is very low (or negative) and what this means is that market rates are not particularly high even though the Fed funds rate may be.

Let me repeat this if you're judging monetary policy from the ranking of the federal funds rate or the ranking of the real fed funds rate you are missing most of the action and all of what is most important.

The Fed funds rate is not the sine qua non although some think it is- No economic agent outside of a banking agent is able to borrow at the federal funds rate. When we look at market rates that are the rates that people invest in, or that are benchmark rates off of which people borrow from, these rates are either moderate or below their medians despite the fact that the federal funds rate in nominal and real terms is relatively high. That's because the yield curve has compensated for the high federal funds rate by being inverted and by having securities yields low. The exception to this is the bank prime rate that stays stuck pretty close to money market rates and the federal funds rate

People who are judging the tightness of Federal Reserve policy by looking at the federal funds rate are completely and totally missing the main points of the economy. And there's another way that we can see this, and that's by looking at what the federal funds rate ‘does,’ that is the impact it has on the inflation rate.

The plot of the CPI year-over-year and the core CPI year-over-year both show that the declining phase of the inflation rate has really hit a slowdown. Inflation is no longer falling rapidly and in fact it may not be falling at all anymore. Yet the inflation rate remains above the Federal Reserve's target. The Fed defines its target in terms of the PCE, and I have plotted the CPI here because the CPI is the inflation rate that is the most up to date we do not yet have PCE data for August.

Preparedness requires preemptive rate cuts before 2% is reached…really?

The Federal Reserve has argued during much of this that it's going to have to start cutting rates before it gets to the 2% level because it does not want to undershoot- (but 40-plus months of over shooting was OK?). That statement is about momentum. Look at the chart above… there's almost no downward momentum for the drop in inflation. The Federal Reserve clearly does not need to start reducing the federal funds rate now, because it's afraid of undershooting. In fact, I would argue that because the Fed has been above its inflation target for so long it needs to make sure it gets to 2% rather than to assume that any kind of decline in the inflation rate is going to continue from here on out. The data are quite unclear about whether inflation progress is going to continue or not. Moreover, if the Fed takes its time to reduce inflation by cutting interest rate now, it's going to reduce the downward pressure on inflation and whatever inflation progress we have been seeing is going to slow down even further

In short, the Fed’s argument about how the inflation process works appears to be completely theoretical and totally disjointed and decoupled from what's going on in our actual economy.

The Fed’s argument unmasked…

The Federal Reserve is arguing that it's in a car going 50 miles an hour and approaching an intersection, as it gets into the no man's zone coming into the intersection it's not quite sure if the light is going to change yellow to red, or not. The Fed's concerned that if the light changes it will need to slow down so that it can stop in time. It argues that it needs to reduce its speed ‘now.’ As a statement about those circumstances, all that is very reasonable… except when we look at the application to the current situation the ‘car‘ is not moving fast. In this example ‘the car’ represents the speed of the decline in the inflation rate. For a while inflation dropped very rapidly, but now inflation is dropping very slowly. It may not be dropping anymore at all. The idea that this faded momentum requires the Fed to begin to engage in breaking now (cutting interest rates) makes no sense whatsoever because the inflation rate is over the target and it's dropping at a very slow speed. The Fed is making a theoretical argument that sounds good on paper that has no applicability to our reality.

In terms of looking at the federal funds rate relative to past circumstances and arguing that it's high… the table above makes the point that market rates compensate substantially so that to the extent that the Fed is higher than it might normally be, market rates have compensated and they're much lower so that the impact on the economy is actually substantially muted. Policy is not anywhere near as tight as what judgments from the federal funds rate might seem.

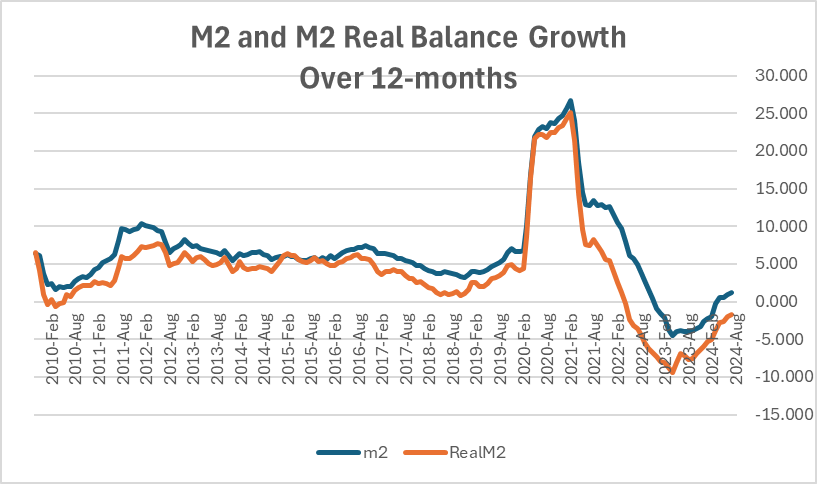

If we look at money growth rates, we can see the M2 growth rates are still quite low they've recovered from the worst of it but nominal money growth is still very weak and real money growth is still declining year over year.

.

If we admit the money growth affects the economy with a lag, we can look at the average money growth over the last year or two years or three years and there what we see when we look at longer lags, is that money growth situation does improve but it still isn't strong or excessive. It's not as weak as it is if you look at 12-month growth rates alone but there's nothing in the money growth statistics that suggest that the growth in the economy is about ready to implode. Money growth is weak, but improving.

Money growth is under repair, and it is picking up, and so it's hard to see anything on the money growth profile that's suggesting the economy is in trouble and the Fed needs to reduce interest rates now. If there was a period during which the economy was at risk to weak money growth that period has passed.

The Fed’s decision for a September rate cut

The decision by the Fed to cut interest rates in September is substantially a decision by the Fed made to cut interest rates in order to make sure the economy doesn't slow too much which will also act to keep the inflation rate from falling as much as it otherwise would, at a time that the inflation rate is over the top of the target for 40-plus months running. It that a good choice?

That's the choice the Fed makes. The question really is whether the weakness in the economy justifies the Federal Reserve running out the string of excessive inflation for another number of months in order to make sure that the economy doesn't weaken excessively at a time that the economy appears to be fairly well balanced, although it has undergone some substantial slowdown in the rate of job growth.

The Fed’s choice revealed- In short, the Fed's choice tells us a lot about what risks the Fed sees and discounts as the greatest priorities. Although the Fed is the central bank and you might think its priority would be to hit its inflation target, the Fed seems to have placed the job market in a higher position than achieving its inflation target at least in the short run. The Fed seems quite content to continue to promise that it will eventually hit an inflation target that it will not prioritize while it will prioritize taking actions in the short run to bolster the job market even when unemployment rate seems to be at full employment. A curious choice…

These are not the decisions I would prefer to see a central bank make. I would far prefer to see the central bank prioritizing hitting its inflation target. The reason for this is simple it's that if inflation gets out of control it can take decades to get back under control. Prioritizing job growth in the short run is a poor choice by the central bank. We have substantial experience with recessions and if the economy doesn't have great problems to be rectified, recessions tend to be short and shallow and not as disruptive. But if the Federal Reserve is unwilling to take the steps necessary to reduce inflation to its target, inflation has a way of ramping up and becoming embedded in people's expectations such that an inflation rate that might have been controlled relatively easily in the short run becomes a much more nettlesome and destructive thing to control in the longer run. We saw how that worked from the mid-1960s into the 1980s.

The 2% or ‘almost 2% dilemma- The Fed asserts that inflation expectations are anchored. The median of the U of Michigan survey is steady at 31% but the mean is over six percent! Yikes! The cut off for the top 25% of the distribution of expectations is at 5.1%. You can’t just ‘throw out 25% of the expectations, for God’s sake and say the median is 3.1% and everything is fine! The width of the distribution that holds the middle 50% of estimates is exceptionally wide, further arguing that expectations are scattered not anchored. If they are scattered, the Fed should be DOUBLING its efforts to convince people it is focused on 2% now… not maybe 2% some time later…

Let’s look at the ‘record’

The record shows the Fed’s record above. It has been above the target only 33% of the time since targeting began. But post-covid rates are above target 95% of the time…Before Covid, inflation was above target only 9.4% of the time. (The designations and cut offs for Covid, pre-Covid and post-Covid are somewhat arbitrary to set different time horizons. These results are not really sensitive to where you set these dates). The point is that once inflation went above target the Fed did not really try hard or aggressively to return it to target- leaving the impression, if we judge the Fed by its actions, that the inflation target is not really important and perhaps no longer valid. This is despite Mr. Powell’s saying the Fed still supports it. What does it mean to support a goal you do not reach when you have the power to reach it?

The Powell Fed; its Choices

The Federal Reserve under the chairmanship of Jay Powell has made a set of choices I think it may regret. We saw scenarios substantially like this in the mid 1960s play out when the Fed was unwilling to keep interest rates high to reduce inflation back to its level and to instead be content with taking the top off of inflation and letting it cool off but reside at a higher level than it was at before the Fed began raising rates. The Fed is essentially doing that again but this time with an inflation target explicitly in place and allowing inflation to continue to run over that target arguing that it will get the inflation rate back to that target eventually but, will it?

An essential question, but NOT the only issue- That's the essential question: “Will it?” But, if the Fed does not have the backbone now to take the risk with unemployment to reduce the inflation rate to target, what makes us think that we'll have the backbone to do it later on? Moreover, the COVID period reacquainted us with the danger of having expansionary fiscal and monetary policy operating at the same time. The Federal Reserve is making these choices in a presidential election year where the election is very hotly contested. Cutting interest rates ahead of the election without a clear reason for it is going to open the Fed up too allegations that it's political. Of course, we know the Fed will deny that it's political and will say that there are never any political statements ever made in FMOC meeting. But that still will not answer the question. Th real problem lurking here is that both candidates have expansionary fiscal agendas and cutting rate now ignores that and set monetary policy up for abject failure in 2025.

The Fed - especially at this time - needs to make monetary policy that is beyond reproach. Instead, the Federal Reserve is making monetary policy that is beyond defense. The idea that the Fed is cutting interest rates as a risk management tool makes no sense whatsoever. It's just one of those vacuous arguments that the Fed will make. It sounds good but it doesn't apply to this situation. Recent economic reports have been solid the Atlanta Fed GDP-Now estimate is at 3% for Q3. Weak? No – no way!

The big problem faced by the Fed is that both political candidates are planning to take actions that are going to enlarge the budget deficit in the year ahead and this is not the time that the Fed should be setting the stage for rate reductions ahead of what promises to be a period of fiscal stimulus. It is highly likely that the Fed is going to have to turn around and unwind this easing much more quickly than it expects (or pretends). And that's because inflation is already over target and when a new president begins to implement his or her new agenda, there will be more fiscal stimulus, there will be more spending, and there will be more inflation. There will not be less inflation. If the Fed does not take care to hit its inflation target very soon it may find that we continue to run over the top of our 2% target for an extremely long period – the timeline is already long. That will be very destructive to the process of inflation targeting. How long can a central bank keep missing a target and contend that the target is still valid?

The Fed is already at the point where we must ask what’s the problem? Is the Fed technically incompetent-unable to figure out how to hit is target? Or is the Fed without the backbone, the desire to hit the target? Or does the Fed have other objectives either (a) political (b) or policy-related that it puts above its inflation goal? We know that the Fed knows how to reduce inflation so it is not a matter of technical inability. And as to ‘will’ we can (for now) take the Fed at its word that it is no taking political sides. That leaves other policy objectives. We know the Fed has a dual mandate and it has a separately expressed desire for a soft landing. Some combination of focus on these goals explains why the Fed is missing its 2% goal. But over the past five years or so with the exception of a giant disruption from Covid that blew the labor market apart, there was a return to full employment. The Fed has hit its full employment/maximum job growth objective again, and yet has consistently vastly overshot its inflation goal. Inflation has been under 2% only the first two months of what I designate as the Post Covid period. The PCE has averaged 4.4%- twice its target. So, looking backward what do you think markets will think of the Fed’s so-called reaction function? What number would YOU fill in the blank for expected inflation when the Fed says it has a 2% target…probably not 2%. Not after this performance.

The obliteration of the 2% target

Once markets realize that when the Federal Reserve expresses something as a target for inflation it will not stick to it, and that it will not ensure that we get to that target in short order, markets will realize that the target is not real. Despite Powell reaffirming ‘it,’ the target will be destroyed.

Bernanke’s Stumble

This is the aspect of this process that I think Ben Bernanke did not think very carefully about. Bernanke saw The Fed with the ability to hit 2% inflation and the backbone to do it and thought it had an ability to express this to the public and that would put everybody on the same side of heading for 2% inflation and that would cause 2% to occur in the future much more consistently.

I think as far as that argument goes it's correct. However, the problem is this: what if the Fed stumbles? What if inflation rises above its target as it has for the last 40-plus months? 40 months is a long period of time, and the Federal Reserve allowed inflation to rise very high over its target for a year…before it did anything-and I mean anything at all. The Fed waited a year before it even reacted to excessive inflation. When the markets reconsider the Fed and the Fed having an inflation target they're going to recognize that this is how the Fed behaved when inflation went awry. They're going to realize that 2% is a lip service target. It’s not a real target. The Fed will not defend it. And so it will not implement it.

This is the problem that the Fed is setting out for itself and one that is getting worse every day, every month, that inflation remains over 2%. It's another month that the Fed's credibility is eroded. People can say ohh it doesn't matter as long as the Fed gets to 2%. But that's completely wrong!!! Every day that the Fed does not get to 2% is another day that inflation is above 2% and that the experience companies have is an experience of above 2% inflation rather than an experience with 2% inflation. And 2% was a number that they had depended on that; they had counted on that; they had planned for that.

Continuing to miss its inflation target is a really big deal and the Fed doesn't even begin to understand it. The Fed is focused on a soft-landing and not disturbing the unemployment rate. It’s the WRONG GOAL!

The Fed has really mixed up its priorities. And in mixing up the priorities it is going to make it harder for the Fed in the future to execute appropriate monetary policy, because people right now are engaged in a process of understanding the Federal Reserve and understanding what the Federal Reserve means by a 2% target. And what it seems to mean is anything goes. The Fed is actively establishing its reaction function, and that function has NO REACTION to over-target inflation until it becomes a serios problem!! The Fed does not react to PCE>2% per se. And markets are realizing what the Fed means by a 2% target is something much higher. And if that's what the Fed wants, that's what the Fed's doing. But if Fed Chair Powell thinks that he can continue to miss this target and continue to say that the target is valid and he intends to hit it, and that that preserves the target, he is only fooling himself. He's not fooling anyone in markets. He is not fooling anyone who has to price securities or make economic decisions in this economy. He is not fooling a large group of people who contribute forecasts to the University of Michigan survey that looks for inflation expectations five years ahead. At least 25% of those people are scared to death. Even more have less elevated but clear concerns. The Fed deals with this reality by ignoring it and looking only at the median for that survey. And yet the median is also elevated when looked at by ranking, but its numerical value of 3.1% seems much more friendly to the Fed. But it is not. The 2% inflation target has become a joke. Take my inflation target…please!